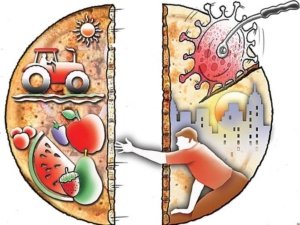

As the pandemic disrupts food supply, cities worldwide are thinking of urban farming as a solution.

As the pandemic disrupts food supply, cities worldwide are thinking of urban farming as a solution.

Access to healthy and affordable food is an age-old challenge for urban residents, especially the poor, from Mumbai to New York. The COVID-19 outbreak has further highlighted the fault lines in urban food systems.

In India, since the lockdown began in March-end, supply of fruits and vegetables from distant peri-urban and rural areas to the cities has slowed. Agricultural migrant labourers have gone back to their home towns and States, disrupting production.

Over-reliance on a centralised supply chain has aggravated the situation. In Chennai, the declaration of the Koyambedu wholesale market a COVID-19 hotspot resulted in a city-wide disruption of vegetable and fruit supply.

Complex repercussions

This situation reveals the complex repercussions of delinking and distancing of food producers and consumers.

To top it all, more than the virus outbreak, the loss of livelihood is posing a bigger threat to thousands of urban poor who now struggle to feed themselves and remain dependent on relief supplies by governmental and non-governmental agencies.

Newspaper articles and reports seem to highlight how those involved in some form of farming or gardening in cities are in a better position to cope with disruptions in food supply. A resident of Noida with a kitchen garden explains in a recent newspaper article, “[A]t first it was just a hobby but when I saw the risk of resources depleting at supermarkets and also that exposure to fruits and vegetables may increase chances of coronavirus transmission through the surface, I thought it might be a good idea to be self-sufficient.”

Many nations are also beginning to think about more sustainable and regenerative urban food policies. Singapore, which currently imports more than 90% of its food, is aiming to meet 30% of its nutritional needs locally by 2030, heavily advocating urban gardening to support this cause.

As such, there is a growing recognition among citizens and governments alike that urban farming and gardening can be an important “shock absorber” and must be the centrepiece in our reimagination of a more resilient urban food system. But a resilient system needs to be equitable too.

Advocating urban gardening among those who can afford it, without integrating vulnerable groups in the plan for a resilient and transformative food system will have limited impact. As such, the Chennai Resilience Centre, a unit of the Centre for Urbanisation, Building and Environment (CUBE) raised by the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras, and the Tamil Nadu government as an applied research, technology and consultancy centre, is working towards fostering an urban horticulture initiative in schools and homes across all socio-economic strata.

Most important, this initiative will include skill development programmes for the lower-income groups to offer them livelihood opportunities in gardening, food processing, and retail and marketing. The hope is to build a sustainable local food production-distribution system while strengthening the capacity of the urban poor.

Similar efforts worldwide can transform the current pandemic into an opportunity to move towards a resilient future for all.

proy@okapia.co

This article appeared in The Hindu titled ‘Produce of the city’ by Dr Parama Roy dated Aug 09, 2020

![]()

Read the original article here:

[visual-link-preview encoded=”eyJ0eXBlIjoiZXh0ZXJuYWwiLCJwb3N0IjowLCJwb3N0X2xhYmVsIjoiIiwidXJsIjoiaHR0cHM6Ly93d3cudGhlaGluZHUuY29tL29waW5pb24vb3Blbi1wYWdlL3Byb2R1Y2Utb2YtdGhlLWNpdHkvYXJ0aWNsZTMyMzAyNTg0LmVjZSIsImltYWdlX2lkIjotMSwiaW1hZ2VfdXJsIjoiaHR0cHM6Ly93d3cudGhlaGluZHUuY29tL29waW5pb24vb3Blbi1wYWdlL3Jxb3R1MC9hcnRpY2xlMzIzMDI1ODguZWNlL0FMVEVSTkFURVMvTEFORFNDQVBFXzYxNS9PcGVuUGFnZSIsInRpdGxlIjoiUHJvZHVjZSBvZiB0aGUgY2l0eSIsInN1bW1hcnkiOiJBcyB0aGUgcGFuZGVtaWMgZGlzcnVwdHMgZm9vZCBzdXBwbHksIGNpdGllcyB3b3JsZHdpZGUgYXJlIHRoaW5raW5nIG9mIHVyYmFuIGZhcm1pbmcgYXMgYSBzb2x1dGlvbiIsInRlbXBsYXRlIjoidXNlX2RlZmF1bHRfZnJvbV9zZXR0aW5ncyJ9″]

© Sumithra Srikanth

© Sumithra Srikanth © Gayatri Ramachandran

© Gayatri Ramachandran Special Arrangement

Special Arrangement Special Arrangement

Special Arrangement © The Organic Farm

© The Organic Farm © The Better India

© The Better India Kalpana Manivanan

Kalpana Manivanan © Indra Gardens

© Indra Gardens © The Better India

© The Better India